By William Crawley, Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London.

William Crawley was invited by the Bangladesh High Commissioner in London to speak at the commemoration of the anniversary of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s birth one hundred years ago. The event was due to be held on the 24th March at the Royal Geographical Society. Due to the current coronavirus crisis, however, the event has had to be postponed indefinitely, though the Bangladesh High Commissioner Saida Muna Tasneem and her colleagues are planning other events later in the year. Below is William’s presentation.

The events which gave an indelible place in history to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the ‘father of Bangladesh’, took place just under fifty years ago. They will no doubt be marked, celebrated, and assessed afresh over the coming months by new generations of Bangladeshi nationals, born after Sheikh Mujib’s death. Scholars and analysts of Asian and international affairs will again be reassessing his legacy. The emergence of an independent Bangladesh was, without a doubt, as Sheikh Mujib himself recognized, the high point of that legacy and the one of which he was most proud.

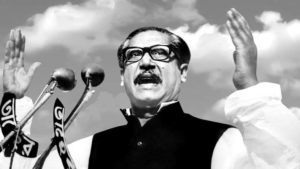

As a new recruit to the BBC External Services radio services, better known as the BBC World Service, in November 1970, I had a small part in the reporting of the events which marked Sheikh Mujib’s crowning achievement, and in analyzing the events that followed up to and beyond his assassination in August 1975. I did not know him personally, but I saw his public and political personality in action at an election rally near Dhaka in 1973, and I took part in an interview with him for the BBC Bengali service on one occasion when he was passing through London as prime minister. I was able to see the charisma that he brought to his nationalist convictions and aspirations, and the admiration he inspired in his followers. What I can bear witness to is the way Sheikh Mujib emerged from the relative obscurity of a provincial East Bengali politician within the context of Pakistan, into the international limelight. He shattered Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s dream – and 25 year achievement of a united Pakistan. I would like to say a few words about the media coverage of these momentous events and the people who contributed to the BBC’s reporting at the time.

The unfolding crisis had begun with a natural disaster, the cyclone which devastated East Pakistan in November 1970.

The BBC’s man on the spot in Dhaka when the cyclone struck was ABM Musa. Musa was attached to the BBC External Services newsroom, not to the Eastern Service (of which the Bengali Service was a part), though both were based in Bush House in Aldwych, a building now occupied by Kings College London. The BBC was the first to report that there had been a disaster in the coastal area of East Bengal. Many years later, Musa recalled this as the moment when the popularity of the BBC in Bengal really started to increase. Brian Barron, a very experienced foreign correspondent, was sent to Dhaka from Singapore to cover the story. The extent of the devastation and the inadequacy of the relief effort was extensively covered in the international media. It was by no means the first such disaster in East Bengal. There were reportedly pleas to the foreign media by the veteran journalist and former editor of the Calcutta Statesman, Ian Stephens, to retain a sense of perspective on the disaster. Despite this, the political implications were far reaching.

The election in December 1970 and the decisive victory in East Pakistan of Mujib’s Awami League underlined a wider importance of the BBC. “Sheikh Mujibur Rahman …was introduced to the world by the BBC”, Musa recalled. Musa was at that time also correspondent of The Times and The Sunday Times, and through them was appointed to the then newly established Asian News Service based in Hong Kong.

Sheikh Mujib’s arrest and the crackdown on society and political activity by the military regime in East Pakistan solidied him as a household name in the international media. Of the British journalists, Simon Dring of The Daily Telegraph had managed to evade the expulsion of foreign correspondents and reported for his paper and for The Washington Post for several days on what was happening; Martin Adeney had been in Dhaka for The Guardian. Peter Hazelhurst covered phases of the story for The Times. The Pakistani journalist Anthony Mascarenhas, sent by the Pakistan government to report on the situation, defected and wrote a powerful first hand expose of the army repression for The Sunday Times. Some weeks later, the distinguished American correspondent Murray Sayle wrote an influential report in the same paper. The BBC World Service and the Bengali Service interviewed others who had managed to leave East Pakistan and their testimony both undercut local censorship and internationally added to a damning picture of the Pakistani army’s role.

In London there was frenetic activity by multiple disparate groups of Bengali supporters of an independent Bangladesh. At a meeting in London, Justice Abu Sayeed Chowdhury, Chancellor of Dhaka University and later President of Bangladesh, became the standard-bearer for many of these groups who had converged on the capital. It is interesting that Sheikh Mujibur’s unfinished memoirs, which were written in 1967, and published in English in 2013, mention Justice Chowdhury’s role in 1946 and 1947 as a prominent student leader who was respected as a mediator between rival factions of the Muslim League in Bengal.

Justice Chowdhury had been at a meeting in Geneva at the time of the crackdown and had been so appalled at the killing of students that he came to London and declared his support for the Bangladesh movement. Packed meetings were held in support of Bangladesh involving senior British political figures such as Fenner Brockway and Peter Shore, both former Labour ministers. The Scottish Liberal MP Russell Johnston spoke in parliament. Elsewhere – not in Britain – Sheikh Mujib – in jail and incommunicado in Pakistan– was proclaimed interim President of Bangladesh and titular head of a government in exile. The headquarters of that government was said to be in ‘Mujibnagar’ which we believed to be a largely mythical place, either on Indian territory or on Bangladeshi territory under Indian control. The BBC followed these events closely and reported them to East Pakistan and to the world. A flood of Bengali refugees into India over the months that followed kept the story in the international headlines.

ABM Musa’s successor as BBC correspondent, Nizamuddin Ahmed, reported on events in the province as far as he could, though for his own protection his name was not attached to the despatches when broadcast. That precaution proved tragically inadequate. He was killed in December 1971, along with a group of prominent Bengali intellectuals, by irregular Pakistani militias known as razakars, on the eve of the capture of Dhaka by the Indian army and the Bengali Mukhti Bahini.

The 1971 war between India and Pakistan and the defeat of the Pakistan army seemed to many observers at the time to have already made Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, isolated as he was, a part of history, barely relevant to what had become an international conflict.

His release and flight to London on 8 January 1972, in a Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) plane arranged by the new leader of West Pakistan, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, restored him immediately to the centre of the political stage. After meetings with the British prime minister Edward Heath and Harold Wilson, then Leader of the Opposition Labour Party, and a meeting with the Indian High Commissioner Apa Pant, Sheikh Mujib gave a memorable press conference in Claridge’s Hotel in which he was questioned in detail about his present position and that of an independent Bangladesh.

My BBC colleague Serajur Rahman crouched next to Sheikh Mujib throughout the press conference, holding a microphone to ensure that the BBC could record and broadcast the historic occasion. To his and our dismay, he discovered when he returned to the BBC studios in Bush House that he had forgotten to switch the microphone on and the tape was blank.

A puzzle to us in the BBC and other news organisations at the time was to what extent Sheikh Mujib could have been briefed after his arrival in London as to what had happened during his incarceration. We believed that he had known very little. Before his arrest he had been negotiating on the basis of provincial autonomy for East Pakistan. Although he had written a declaration of Bangladesh’s independence before he was arrested, he had no idea whether it had reached his followers or whether it had been acted on. He had been declared interim President by the Mujibnagar government in exile, though his preference was for a parliamentary system of government in which the prime minister rather than a President headed the government. He only had a few hours to absorb the implications of the situation and to confirm his own attitude towards them. Later a respected Bangladeshi journalist wrote in a Dhaka newspaper that some BBC journalists had spread ‘untruthful’ reports about this in order to diminish Sheikh Mujib’s authority and credibility. This was certainly not the case. Whether he had been incompletely briefed or not, it was no reflection on his standing as a leader. Sheikh Mujib’s unfinished memoirs do not cover that transformative moment in his political career.

Some of the interviews that Sheikh Mujib gave after his release are available now on YouTube. A pooled TV interview with a correspondent for the Associated Press shows Mujib smoking his pipe in what we may now think of as a quintessentially English fashion. I was told by my Bengali colleagues that he had always ordered his favourite brand of tobacco – St Bruno – from suppliers in London. In a later interview he spoke to David Frost, then at the height of his TV career in Britain and the USA as a television news anchor. He spoke quite emotionally about the ups and downs of his political career. My own impression of that interview at the time was that for a leader who had built his early career on the promotion and advancement of the Bengali language, it was a shame that he chose to be interviewed in English rather than Bengali with an interpreter. He was of course fluent in English, but not as effective a speaker, and he had a dramatic story to tell.

There is no time to dwell on his record as prime minister and then again President under the later discredited BAKSAL constitution. His death and that of close members of his family in August 1975 at the hands of assassins from within the Bangladesh army was brutal. But it did not overturn his legacy of independence for Bangladesh.

In marking the centenary of Sheikh Mujib’s birth, I have focused on just one part of his life and legacy. There are, of course, much wider historical perspectives on his career. Historians identify several types of narrative covering the independence of Bangladesh. The idea that undivided India contained two nations – Hindu and Muslim – was nominally achieved in 1947 with the creation of two states, Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. The breakup of Pakistan in 1971 effectively negated that narrative. An earlier perception was one that for a time had been promoted by the Bengali leader Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy. That was a belief in Bengali identity and Bengali nationalism based on a shared language and culture, with a territorial reach that included the whole of Assam and what became Indian West Bengal, including the city of Kolkata. For a time the young Sheikh Mujib, as Suhrawardy’s political disciple and aide, had shared his mentor’s vision. This concept of two independent Muslim-majority ‘Pakistans’- one in the west and one in the east – was emphatically rejected both by Jinnah and the Congress. Suhrawardy later became prime minister of Pakistan for a brief year in 1956-57. But the language movement in East Pakistan echoed some element of that earlier vision and it surely formed an important part of Sheikh Mujib’s political outlook.

The lessons that Mujib’s career illustrated from the start were the importance of regional languages and political power. The re-drawing on linguistic grounds of state boundaries in independent India had also underlined that compulsion. For the media there were two overriding lessons. One was the counter-productive effects of state censorship in managing a political crisis. A second was the real dangers to journalists in reporting not only war but bitterly contested civil conflict. In the years since, these dangers have only grown.

Finally, I think it is remarkable that the same issues of language national boundaries and contested cultures that marked the partition of India in 1947 reappeared in 1971. Both Jinnah and Nehru saw the legacy issues of language national boundaries and contested cultures of the states that they led as incomplete. Gandhi, the ‘father of India’, never accepted partition until his death. For Jinnah, the ‘father of Pakistan’, it was a ‘moth eaten’ Pakistan that left millions of Muslims in India. For Nehru – India’s first prime minister – it was a partial and truncated ‘tryst with destiny’. Sheikh Mujibur, the ‘father of Bangladesh’, established an independent Bengal. But he did not attempt to challenge the boundaries inherited from East Pakistan that as a young man he had hoped, with his mentor Suhrawardy, to shape so differently.

The Commonwealth Oral History Project at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies includes interviews with Dr Kamal Hossein and David McDowell which provide further insight into the tumultuous events around the emergence of independent Bangladesh.

Recent Comments