Dr Balasubramanyam ChandramohanSenior Research Fellow

In India the start of World War 1 generated a great wave of enthusiasm, commitment and mobilisation of taxes, and voluntary donations by individuals and the rulers of princely states, an ‘almost universal loyalty’

People, money and materials were mobilised: 1,200,000 men (800,000 of whom were combatants), £100 million outright and £20-30 million annually, not only to defend India, but also to fight alongside the Allied forces across different fronts overseas. More importantly, the political leaders, including Mahatma Gandhi, were also supportive of the War in the hope that Indians would get a greater say in the running of the country, a greater level of self-rule, as a reward for the loyalty and support once Britain wins the war. There was no conscription, but a large number of people joined the army to fight in the War.

April 1916, Indian troops replacing 10,000 British troops captured at the Battle of Kut-al-Amara by the Turks

As the War progressed, disappointment at the perceived lack of sufficient progress on self-rule, war-time economic changes, social and cultural changes caused by the churning of the War, and political mobilisation of different strata of society (and the government’s strategies to manage them), led to the rise of identity politics of religion/caste/language-region during and after the War. There were expressions of dissatisfaction, not always within the law. The War resulted in constitutional and governance arrangements that accommodated, but also contributed to, the articulation of nationalist and sub-nationalist identity politics, leading, eventually, to the emergence of India and Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

Within India, these arrangements contributed to linguistic reorganisation of states and constitutional provision for ring-fenced political representation, as well as social and political advancement of marginalised castes and tribal populations. It is now largely forgotten that close to 1.3 million Indian soldiers served in World War 1, and over 74,000 of them lost their lives. Memorials in India for the Indian troops who died in the War include:

* Delhi (The Delhi Memorial — India Gate)

* Delhi (Teen Murti Memorial)

* Kolkota (Calcutta): Bhowanipore Memorial, Cenotaph Memorial, Memorial to the 49th Bengal Regiment, Lascar Memorial

* Chennai (Madras): Victory Memorial (‘Constructed by a committee of prominent and influential citizens of Madras’)

* Mumbai: The Bombay (1914-1918) Memorial (for sailors from India, Aden and East Africa)

* Pune (Poona): Kirkee War Memorial.

There are also memorials outside India in Europe, Africa and the Middle East that underline the diverse theatres of war in which troops from India fought.

Although these memorials were built to memorialise the soldiers of World War 1, they also served to memorialise the participants in later wars during and after the colonial period, a trend that can be noted in monuments in other countries too. War memorials reflect not only the chronology of events but also the nature of warfare. They also embody contemporary concerns of later periods and inclusivity in terms of social divisions such as gender and region, recognising heroism on the battle fields as well as that of the home front.

War memorials, ceremonies and memorabilia also serve to symbolise changing relationships of combatants and their descendants to past historical events and personalities. For example, the Making a New World exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London narrates the story of the war in a manner that captures the experiences and views of a broad range of people, including that of Kaiser Wilhelm II in July 1914: If we are going to shed our blood, England must at least lose India.

Post-colonial India’s memorialisation of World War 1 has varied between acceptance of the memorials (that included letting the Commonwealth Graves Commission maintain some War Memorials that honoured the fighters of the World War and finding new uses for memorials and memories. The India Gate memorial, for example, provides the venue and backdrop for celebrating the sacrifice of the war dead, but also for demonstrating the military prowess of contemporary India during the Republic Day celebrations. The Teen Murti Memorial Chowk (Square) in New Delhi that celebrates the victory of three cavalry regiments from India in the battle for Haifa was renamed Teen Murti Haifa Chowk in 2018 reflecting, symbolically, India’s changing international relations with Israel.

The Ministry of External Affairs (Government of India) and the United Service Institution of India have jointly undertaken the India and the Great War Centenary Commemoration Project (2013) in order to, among other goals, ‘use the centenary commemoration of the Great War as a medium to emphasise the sterling contribution made by the Indian Army towards the establishment of world peace’.

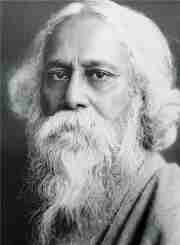

Memorialisation is about selective remembering, but that not infrequently includes selective amnesia, as David Olusoga documents the ‘forgotten soldiers of empire’. It has been argued that, for a variety of reasons, the contributions of India and Indian soldiers have not received their due recognition, for example, by Shashi Tharoor and Aditya Iyer. However, they also acknowledge that the authors Mulk Raj Anand, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sarojini Naidu deal with the War in their literary works.

Perhaps the most enduring of India’s contributions to World War 1 is cultural. It is a poem by Tagore that appealed Wilfred Owen, arguably the best known British poet of World War 1. Tharoor narrates:

Indian literature touched the war experience in one tragic tale. When the great British poet Wilfred Owen (author of the greatest anti-war poem in the English language, Dulce et Decorum Est) was to return to the front to give his life in the futile First World War, he recited Tagore’s Parting Words to his mother as his last goodbye. When he was so tragically and pointlessly killed, Owen’s mother found Tagore’s poem copied out in her son’s hand in his diary:

When I go from hence

Let this be my parting word,

that what I have seen is unsurpassable.

I have tasted of the hidden honey of this lotus

that expands on the ocean of light,

and thus am I blessed

— let this be my parting word.

In this playhouse of infinite forms

I have had my play

and here have I caught sight of him that is formless.

My whole body and my limbs

have thrilled with his touch who is beyond touch;

and if the end comes here, let it come

– let this be my parting word.

Recent Comments