by Keith Somerville, Senior Research Fellow

School trips to the Commonwealth Institute in Kensington made the Commonwealth more tangible for Keith Somerville

My first memory of being aware of something called the Commonwealth was as a six or seven year old at West Acton Infant’s School in West London. On the second Monday in March, if the weather was good, the whole school would line up in the playground by a flagpole from which the union flag was fluttering. We’d then be talked at by some dignitary or other (possibly the local mayor or an MP) about the Commonwealth and its importance as the successor to the great British Empire. As I dimly recall, the speaker would talk about brotherhood, cooperation and love among nations. That meant very little to a child of that age, but after singing the national anthem, we all got the rest of the day off.

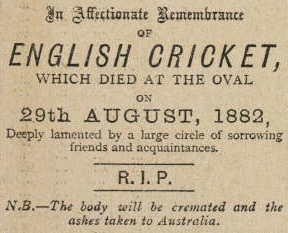

As I grew up and became interested in history and geography, the Commonwealth would crop up when we studied, say, human geography about cocoa farmers in Ghana or population issues in India. The textbooks we used and our teachers would remind us that we were part of some greater community of people who shared some sort of heritage – though of course in the 60s and early 70s there was no serious examination of that heritage having come about because of the invasion, occupation and exploitation of other countries by the British; and then the belated attempt to do a makeover by stressing brotherhood and cooperation (with an implicit background theme of joining together in happy union to keep down the fearful Ruskies and their terrible commie allies). For me, as a keen cricketer, it was obvious that the Commonwealth was very important, as only Commonwealth countries played cricket – so must be fine chaps! Apart from the South Africans, of course.

The Commonwealth took on more tangible form when I was in the sixth form at St Clement Danes Grammar School. We went on trips to the Commonwealth Institute in Kensington, which I found fascinating, and got a still rather sanitised but marginally more realistic view with some issues of post-colonial political and economic development alluded to above. I became more interested as, by then, I had a growing fascination with southern Africa and things like the Zulu and Boer wars. Coming from a family where politics was a daily topic for discussion and passionate debate, I soon learned from my trade unionist father that these wars weren’t glorious examples of British grit and determination but part of a whole process of colonial expansion and greed.

For a keen cricket fan like Somerville, it was obvious the Commonwealth was important, as only Commonwealth countries played cricket

By the time I was at university in the mid to late 1970s, the Soweto Uprising had sharpened my interest in South Africa and led me to join the Anti-Apartheid Movement. The Commonwealth’s relevance was now clear in another way – as a grouping of states which could be used to bring pressure to bear on the British government and UN over both apartheid and white-minority rule in Rhodesia. But while Commonwealth diplomacy was important, it had its limits and resistance from Margaret Thatcher reduced the ability of the Commonwealth to have a decisive effect. Nonetheless, it had an effect which was symbolically important.

By the time I had my feet well under the table as a producer and then programme editor at the BBC World Service, the Commonwealth had evolved further in my personal experience – it was a source of interviewees (from the Secretariat, the Institute of Commonwealth Studies or from among commentators and politicians from member countries) on a range of topics from southern Africa, through Nigeria’s judicial murder of the Ogoni activist, Ken Saro-Wiwa to the civil war in Sri Lanka, and Zimbabwe’s land occupations. But the biggest Commonwealth impact, which has clearly lessened in the last decade and a half, was the immense planning for extensive coverage of the biennial CHOGMs (Commonwealth heads of Government Meetings) – which to us seemed to come round more frequently than every two years. Coverage plans and deployment of correspondents (names like Barney Mason, Mike Wooldridge, Mark Brayne and, if on the Indian sub-continent, the almost legendary Mark Tully, or ‘Tully Sahib’ as he was affectionately known).

Now, apart from a flurry of controversy over the holding of the 2013 CHOGM in Sri Lanka, these Commonwealth summits aren’t the big World Service events they used to be. That may of course change after Brexit, if it happens. The Commonwealth could be again reached out to by a Britain desperate for trading partners. Yet again, the Commonwealth will be asked to forgive British behaviour, which will be to the detriment of its members.

Over more than 50 years the Commonwealth has changed in relevance and the way it impinges on me, personally. It has declined in importance globally and now seems little more than a two-yearly social for leaders who might otherwise not meet in a single group. It also seems of little or no relevance to younger Britons. I recently asked my third year and postgraduate journalism students at the University of Kent, Canterbury, what the Commonwealth meant to them and got equally blank looks from British, Ghanaian, Indian and Kenyan students.

Recent Comments