by Susan Williams, Senior Research Fellow

How one addresses the question of the Commonwealth’s relevance depends on one’s perception of ‘the Commonwealth’.

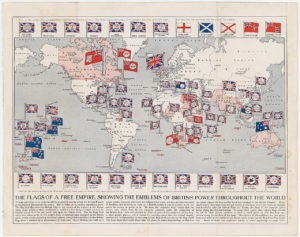

It is known globally as an international association, bringing together 53 ‘independent and equal sovereign states’. But in the UK, it is sometimes called ‘the British Commonwealth’ and is narrowly associated with British imperial rule. This mind-set was apparent during the Rio Olympics in 2016, when a British MP – adding up the medals won by Commonwealth nations – tweeted ‘Empire Goes for Gold’. Such a conception is stuck in the past and holds little, if any, relevance for the present or the future.

The notion of ‘the British Commonwealth’ is out of date by nearly 70 years: for in 1949, two years after the independence of India and Pakistan, the appellation ‘British Commonwealth’ was changed to ‘Commonwealth of Nations’. Membership no longer required allegiance to the British crown. This change was made in response to India’s wish to remain in the Commonwealth, although becoming a republic. The Commonwealth was adapting to the postwar reality, in which Britain was losing its global power.

The struggle to end British rule united its colonies. Resistance movements engaged with each other in intense dialogue: how best could a newly-independent nation create a just and democratic society? This was a complex challenge for territories where the British had seized land and resources, established racial inequalities, and carried out atrocities, pitting different groups against one another. Tactics of resistance, such as civil disobedience and economic boycotts, were shared across the empire. Hopes were also shared. ‘Despite differences of craft and personal politics,’ observes the Kenyan author Ngugi wa Thiong’o, writers in colonial Africa were ‘united by a vision of a different future for Africa.’

In 1957, Ghana became the first British colony in Africa to achieve self-rule and to join the Commonwealth. Its leader, Dr Kwame Nkrumah, stated that he was not opposed to Britain itself, but to British injustice: ‘I am fighting against a system – the system of colonialism, imperialism and racialism – not against peoples.’ Nkrumah believed that the Commonwealth had ‘an important duty to mankind’, especially in the struggle against racialism. Ghana blazed a trail: over the next few decades, British rule ended across the world and membership of the Commonwealth expanded rapidly.

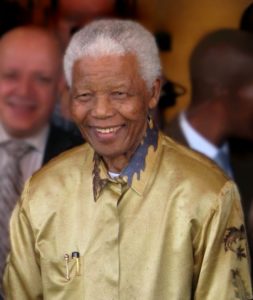

The emerging Commonwealth leadership was assuming a new role: that of informal diplomacy and patient dialogue, as a way of defusing tensions and resolving conflicts. These skills made a crucial contribution to the struggle to end white minority rule in Zimbabwe and apartheid in South Africa. ‘The Commonwealth can look back on that period with pride,’ observes Emeka Anyaoku, the Nigerian who was the Secretary General between 1990 and 2000. ‘We played a key role in the international campaign and in doing so provided a powerful lead to the rest of the world on a key matter of principle’ (quoted in The Commonwealth Yearbook 1999). In 2004 Nelson Mandela expressed his gratitude to Anyaoku. ‘The Commonwealth,’ he said, ‘had earned a place of honour in the gallery of international organisations.’

Following the 1989 Commonwealth heads of government meeting in Kuala Lumpur, a group was set up to determine the association’s future role as it advanced towards the millennium. This led to the Harare Commonwealth Declaration, which was issued in Zimbabwe in 1991. Drawing on the Commonwealth’s shared ideals, it mapped out a fresh course: that of promoting democracy and good governance, human rights and the rule of law, gender equality, and sustainable economic and social development. In 2012, this and other landmark Commonwealth declarations were codified in the Commonwealth Charter.

Today, this voluntary association brings together 2.4 billion people, who are united not so much by the heritage of Britain’s imperial past, as by Commonwealth values. Because of these values, two nations with no previous ties to any Commonwealth country – Mozambique and Rwanda – have become members, and others have applied to join.

The Commonwealth Games are known as the ‘friendly games’. ‘This was the exact atmosphere I felt’, notes Leanne Simoncelli, a physiotherapist from Zimbabwe who treated athletes from all over the Commonwealth at the 2014 games, including from small island nations such as Niue. ‘While working at the London Olympics and European Games,’ she adds, ‘the feeling was fierce competition, rather than the spirit of Commonwealth co-operation and comraderie.’*

But the association faces huge challenges: 60 per cent of its population is aged 29 or under; some member governments do not comply readily with the Charter; and there is a concern that the making of decisions and of policy is undermined by the dominance of some member nations. The role of the British monarchy is an anachronism: although Queen Elizabeth is the current head, the position is not hereditary and her successor must be chosen by the heads of government. The new head should be appointed from the wider world and should embody the egalitarian values and aspirations of the Commonwealth Charter.

The values of the Commonwealth are more relevant than ever. At a time when powerful world leaders are building divisions between peoples, and walls between nations, it seeks to bring together all its member states in one large family – on an equal basis and regardless of race, colour, religion or gender. ‘The Commonwealth,’ believes Dr Tukiya Kankasa-Mabula, a deputy governor of the Bank of Zambia, who has helped to develop the Commonwealth Youth Leadership Programme and is a daughter of two heroes of Zambia’s freedom struggle for independence, ‘provides a platform for communication among peoples with a common heritage in a world that is increasingly becoming insular.’**

* Leanne Simoncelli to Susan Williams, 9 December 2017

**Dr Tukiya Kankasa Mabula to Susan Williams, 22 December 2017.

Recent Comments