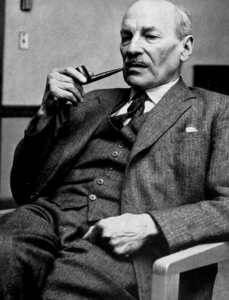

Prime Minister Clement Attlee hosted the 1949 Meeting of the Heads of Government of the Commonwealth of Nations, which laid down the role of King George VI as Head of the Commonwealth

By James Chiriyankandath, Senior Research Fellow

For over a decade I’ve co-edited Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, which is, along with The Round Table, one of the two journals, both published by Routledge, focused on the politics of the Commonwealth. First published in November 1961, twelve years after the emergence of the modern Commonwealth at a time when just thirteen of the current 52 states of the Commonwealth were independent members, its pages have spanned four-fifths of the history of the organisation. So, in considering its contemporary relevance, it might be instructive to regard the way in which contributors to the journal have viewed how the Commonwealth has changed.

However, before doing so, it is worth noting how the very name of the journal reflects how scholars and publishers in politics see the importance of the organisation. It was launched, as the Journal of Commonwealth Political Studies (JCPS), from the Institute of Commonwealth Studies at the University of London, founded in 1949, the same year in which the post-imperial Commonwealth had its inception. The idea for the journal, stimulated by the rapid decolonisation that was transforming the Commonwealth, emerged in the late 1950s out of a seminar series initiated at the Institute by its first director, Professor Sir Keith Hancock, the distinguished Australian historian of the Commonwealth.

In its first two decades, Hancock’s successors at the Institute, Kenneth Robinson and W.H. Morris-Jones, co-edited JCPS, but after the enterprising publisher Frank Cass acquired it in 1974 it was renamed The Journal of Commonwealth and Comparative Politics to give it additional appeal and scope beyond the Commonwealth. This change was reflected in the articles published – the Commonwealth figured in the title of 21 articles published through the 1960s and 1970s but in only six of those that appeared in the 1980s and ‘90s. The decline in scholarly interest was less pronounced but also still evident in terms of how often the Commonwealth was cited in issues – from around twenty or more times annually in the 20th century to about fifteen times or less since 2000.

The Institute of Commonwealth Studies at its first home in Russell Square, from where the Journal of Commonwealth Political Studies was launched

It therefore appears that from the informed perspective of those who study politics the Commonwealth has become less significant over recent decades. What does this mean for its relevance today? In terms of the larger states within the Commonwealth it is not of special relevance for their foreign relations. The question the international relations theorist Martin Wight posed 60 years ago seems even more apt now: ‘I ask whether there is any assertion one can make about the relations of Commonwealth countries inter se which will not be true of the relations between some Commonwealth countries and some countries outside the Commonwealth.’

This is not true for the small states who form a majority of the Commonwealth’s remarkably heterogeneous membership. For them its unique configuration ‘containing both large and developed states in wider and more fluid relationships than in similar international structures elsewhere’ is valuable in mitigating the bilateral patron-client relationships they find themselves in vis-à-vis large Commonwealth states (notably Australia, Britain, India, South Africa and New Zealand).

The sense of a loss of purpose for the Commonwealth was caustically expressed in a 2006 article by Krishnan Srinivasan, a former foreign minister of India and deputy secretary-general of the Commonwealth. Reflecting on Britain’s relationship with it, he wrote: ‘Britain retains substantial Commonwealth infrastructure because there is no one else prepared to pick up the torch and attempt to revitalise the association […] it has become nobody’s Commonwealth.’

What such a judgement fails to recognise is both how the world and the Commonwealth has changed. In a special issue edited by Vicky Randall in 2001, remarkably the only one devoted to the Commonwealth as an institution in the journal’s history, a scholar observed that its potential lay in the realm of ‘soft’ security [power]: ‘in continuing to pursue the high ideals that it already holds, support the work of the United Nations, encouraging human development and championing a more just world’. Others have seen a future for the Commonwealth as lying beyond, or transcending, the traditional world of states and international relations. It may well be that the main relevance of the ideals embodied in the Commonwealth is going to be in contributing to the commonwealth of people and ideas rather than the state-centric post-colonial Commonwealth of the past.

Recent Comments