The BBC documentary, ‘Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners: Profit and Loss’, broadcast in July 2015, shed light on the vast resources appropriated by Britain through the enslavement of African peoples in the Anglophone Caribbean. In addition to the financial impact this genocidal period of world history had on Britain, the documentary also talked about the dehumanisation of African peoples, through discourses, popular culture and European intellectual thought. The legacies of this dehumanisation endure to this day, with people of African heritage in Britain facing racial injustice in many spheres of life. It is in this context that a coalition of Civil Society Organizations in Europe and the Americas Representing People of African Descent have made a number of key demands of the British state.

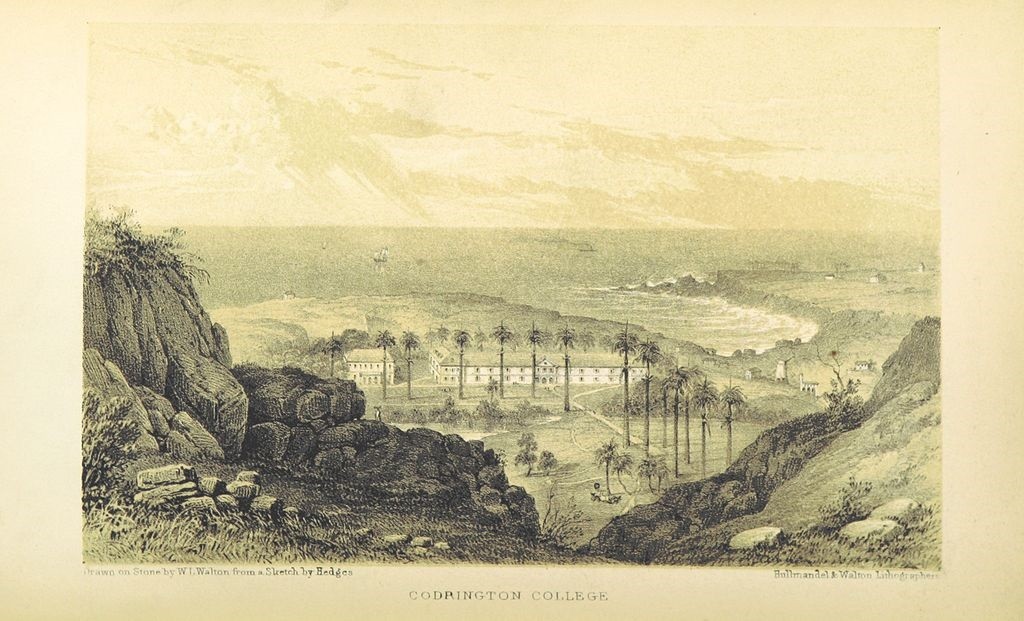

The Codrington Plantations, like many others in Barbados, relied on enslaved labour. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Studies have shown that students of African heritage perform better in blind-marked exams (such as SATS), than teacher assessments, with the opposite being the case for their white counterparts. This indicates an implicit racial bias, in which the intellectual capacity of African heritage students is undervalued across the board. We see these patterns in other spheres of life, none more so than in the criminal justice system. If we take the policing of criminalised drugs, we see that people of African heritage are more likely to be stopped and searched for criminalised drugs, despite studies showing that African heritage and white people consume drugs at roughly similar levels. Furthermore, across a range of offences, people of African heritage are more likely to be arrested than their white counterparts. They are also more likely to be charged, be found guilty in court, receive a custodial sentence, and that custodial sentence is likely to be longer than their white counterparts. We could go on with these contradictions, but we need to do little more than to look at the fact that people who are not racialised as white die at a rate of almost one per fortnight, at the hands of the British state. Where stereotypes about laziness, criminality and anti-intellectualism were created to justify enslavement of African peoples, we see them reproduced today in ways that undereducate and criminalise those same communities of people. As part of our resistance to this violence, a National Injustice Day will be held on the 4th August every year, the day that Mark Duggan was shot dead by the British state.

On the 1st August every year, people of African heritage organise a Reparations March, from Brixton, the beating heart of Africans in Britain, to the Houses of Parliament, the centre of state power. In addition to the British state taking full responsibility for the Maangamizi (African Holocaust) and establishing the month of August each year as the National Maangamazi Awareness Month, we demand a National Commission of Enquiry on the historical and contemporary national and international impact of Britain’s transatlantic traffic in enslaved Africans. An equivalent commission has already been accepted by the Prime Minister David Cameron for Jewish peoples, and we welcome this important and progressive step. Yet, Ottobah Cugoano demanded such a commission for African peoples in the 18th Century, and successive generations have continued this struggle up until today. Reparations is about sustainable development, not cash handouts. It’s about democratic power for our people, not charitable pity. And most importantly, it’s about freedom from all types of domination, from over policing and state brutality, to exploitative working conditions, and a Eurocentric school curriculum. These are the legacies of colonisation, these are the ways in which we suffer, and it is this which must be undone, if we are to realise the liberating potential of genuine, and inclusive reparations agreement.

Recent Comments