By Keith Somerville, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies at the University of London and teacher at the Centre for Journalism, University of Kent. He is editor of the Africa – News and Analysis website.

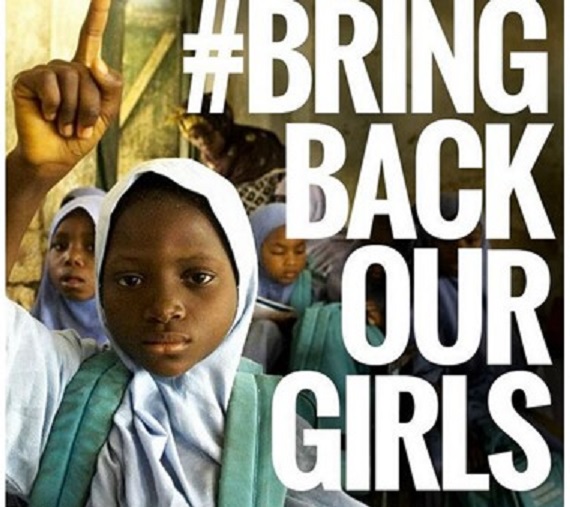

The release of the latest Boko Haram video, appearing to offer a deal for the release of some of the girls and announcing the “acceptance of Islam” by others is the latest internationally-aired twist in the Nigerian abduction story. It follows the announcements that teams of American and British specialists are in Nigeria helping the security forces find the 284 abducted schoolgirls, and the offers of help from China and France to assist, have brought to full international attention a brutal and complex conflict that has been generating fear and suffering in north-east Nigeria for several years. As part of the sudden Western flurry of concern, Michelle Obama will take her husband’s place in making a presidential address on the issue. For the USA, Britain, France and China this is a chance to follow strategic choices while expressing empathy over a humanitarian crisis.

Boko Haram, the group

The abduction of the schoolgirls is a shocking event but only one of many attacks by the Islamist group Boko Haram since their formation in the north-eastern city of Maiduguri in 2002. At least 1,500 civilians (both Muslim and Christian) have died in attacks claimed by the movement since the beginning of this year and many thousands more since it launched its overt military campaign in 2009. The recent bombings in Abuja attest to the reach of Boko Haram. The name by which they are known can be translated as “Western Education is forbidden” and encapsulates their total opposition to anything but a very narrowly interpreted form of education and lifestyle based on Salafist Islamic principles. The full name of the movement – Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad – is translated as “People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad”. They want to see Nigeria become an Islamic state along the lines of their particular interpretation of the religion – an interpretation not accepted by many Muslims in Nigeria and in direct opposition to the traditional practice of Islam in northern Nigeria through the centuries old religious and political hierarchy based on the northern Nigerian sultans and emirs of Sokoto and Kano.

The movement has a loose structure of units spread across north-eastern Nigeria, is well-armed and able to evade capture. Many Nigerians believe that it has the support of former military leaders and politicians in the north who have lost power in recent years and who, while not wanting a Boko Haram-style state, are willing to support or tolerate the movement in order to weaken the current government, led by the southern, Niger Delta politician, President Goodluck Jonathan.

But why does Boko Haram still attract support despite years of attacks on churches, mosques, schools and the killing of civilians in raids and bomb attacks?

Because the young men of north-eastern Nigeria have poor educational or job prospects and live in an area that has not benefited from Nigeria’s oil wealth or from the past dominance of northern Nigerian leaders in politics and in military governments. They feel marginalized, forgotten and resent that they are poor while many other Nigerians are rich through access to education, jobs, contracts, or through corruption or patronage networks. The north-east has always been marginal to the centre of power and wealth. The political, social and religious power of northern Nigeria is situated in the north-western or central-north areas of Sokoto, Kano, and Kaduna rather than Borno, Yobe and Aadmawa states, where Boko Haram is most powerful. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, this region saw extreme violence against civilians by a strange Muslim sect led by a self-proclaimed prophet called Maitatsine. Boko Haram does not claim descent from the idiosyncratic version of Islam perpetrated by Maitatsine followers but does call on the same support base – poor, unemployed and frustrated youths with no reason to thank national or local leaders and every reason to feel frustrated and angry at their exclusion from the exploitation of Nigeria’s wealth. This does not excuse brutal insurgency but it does give some explanation of why this region has been so affected and why people feel that this is an option for them and it explains how leaders of groups like Boko Haram are able to recruit members. Grievance is a powerful recruiting tool among the marginalized and poor.

Nigerian Government’s response

Government counter-insurgency operations have failed to stamp out Boko Haram and have led to massacres of civilians in villages in Borno State as the army has carried out revenge attacks for the deaths of soldiers. Use of force has at times been indiscriminate and has failed to suppress the movement while terrorising and alienating ordinary people. The killing of around 200 civilians in the village of Baga, Borno State, in April 2013 was just one example of a counter-insurgency campaign that was both brutal and unsuccessful and neither rooted out Boko Haram nor won the hearts and minds of local people.

Nigerian Army’s position

The sectional interests of the army also come into the picture. It has long been argued by Nigerian political scientists and commentators that the army has an interest in the continuation of conflict – whether in the north-east, Plateau State or the Niger Delta – as it ensures the continuing reliance of the government on the armed forces and keeps the “security vote” high; that is the allocation of a disproportionate amount of Nigeria’s oil revenues to the military and the maintenance of the wealth and patronage networks of military leaders.

How differently does affect Boko Haram the Western countries and Nigeria itself?

While Boko Haram pledges allegiance to Al Qaeda has links with jihadist movements in Niger and elsewhere in the Sahel, it has not posed a major threat to Western interests so far. But the prominence it has gained through the kidnapping of the schoolgirls has amplified existing Western concerns about the extent to which its insurgency campaign could destabilise the Nigerian government and lead to instability in neighbouring states.

The major threat, though, that is posed by Boko Haram and by the counter-insurgency campaign of the Nigerian army is to the people of the region and its economy. They are the ones suffering, being abducted or being killed by the rebels and the security forces. The video released on 12th May and the announcement that many of the girls had converted to islam and become, in Shekau’s words, “sisters of the militants” will be of little solace to their families as the Boko Haram leader appeared to say that these girls would stay with the movement, though doubtless not of their own accord.

Recent Comments