By Richard Bourne and Helena Whall

The Commonwealth’s First Nations: Rights, Status and Struggles in the run up to the UN World Conference on Indigenous Peoples, 2014 – Conference Programme

Not since Idi Amin’s threat to attend the London Commonwealth summit in 1977, which led to the first statement by leaders denouncing human rights abuse in a member state, has there been such a focus on rights issues in advance of a meeting of Commonwealth heads of government. But the forthcoming Sri Lankan summit will also be a chance for governments to comment on the human rights of an often invisible group of Commonwealth citizens – its indigenous peoples.

Next year there will be a UN world conference on indigenous peoples, the first such event since the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples which was passed in spite of the opposition of four states – the United States, Australia, Canada and New Zealand– which have since ratified it on the basis that it is non-binding. Judging by a preparatory meeting in June this year the conference will focus on indigenous peoples’ concern for their lands, resources, seas and waters; their desire to push on for recognition of their rights across the UN system; and their own priorities for development using, in the words of the declaration, their “free, prior and informed consent.”

At one time it looked as though the Commonwealth was ready to take up the rights of indigenous peoples, now numbering between 180 and 200 millions in all, with human rights issues mentioned in 21 states according to the 2012 cycle of the universal periodic review. For in 1979, at the Lusaka summit which led to an end to the civil war in Zimbabwe, leaders recognised,

“that the history of the Commonwealth and its diversity require that special attention should be paid to the problem of indigenous minorities.”

But the opportunity was lost. In 2003 the Abuja summit ignored a well-prepared proposal from the then Commonwealth Policy Studies Unit (CPSU) at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies to endorse indigenous rights. The CPSU had been working on a project on indigenous rights in the Commonwealth, supported by the European Commission and the UK Department for International Development. The Abuja summit by contrast made two significant advances for rights in the Commonwealth, by supporting freedom of information, and agreeing to add the Latimer House principles – which set out the proper relationship between executive, judiciary and legislature – to the terms of reference for the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group.

demonstrates

the continuing need for action on indigenous rights”

In 2005, at the Valletta summit, the heads of government made an indirect acknowledgement of the greater oppression suffered by half of its indigenous populations – its women. It endorsed a statement adopted by Commonwealth Women’s Ministers, in their Plan of Action for Gender Equality, 2005-2015, that “indigenous women are marginalised and disadvantaged in comparison with other groups and that they face significantly greater poverty.” But it is doubtful how many leaders pore over the small print of such endorsements, let alone resolve on immediate follow-up as they return home.

Yet Sri Lanka demonstrates the continuing need for action on indigenous rights. It has a vulnerable population of around 2,000 Wanniyala-Aetto ( literally “forest dwellers,” described as Veddha by the majority on the island ). Wiveca Stegeborn, the leading academic authority on this community, states that there is archaeological evidence that their forebears were present up to 39,000 years ago. She writes: “As forest land was taken for farming, development projects and subsequently tourism, the Wanniyalo-Aetto were uprooted from their traditional environment and displaced in government Rehabilitation Villages. Government schools were established in these new communities, and Wanniyala-Aetto children were banned from learning their native language, customs, and subsistence srtrategies. Instead they were instructed in Sinhalese, about farming and in the Buddhist teachings.

“In 1982 the Accelerated Mahaweli Development Project ( AMDP ) logged and bulldozed land to make dams for hydro-electric power, artifical irrigation and petr-agriculture. The little forest that was left became the Maduru Oya National Park. Once an integral place for hunting and foraging, the land now became a site of deadly conflict between government officials and displaced Wanniyala-Aetto residents.

“On 9 August 2013, Indigenous People’s Day, President Rajapaksa promised that the Wanniyala-Aetto would be allowed to return to their forest homes without further harassment; he was the fourth president to make this claim and is likely to be the fourth to break it. Unlike Sri Lanka’s Tamil population, the Wanniyala-Aetto are not a formally recognised minority. They stand in the shadow of the widely publicised conflict between Sinhalese and Tamils. A proposed initiative to distribute land to Tamils presents a problem, because the land and resources in question are necessary to the Wanniyala-Aetto way of life….”

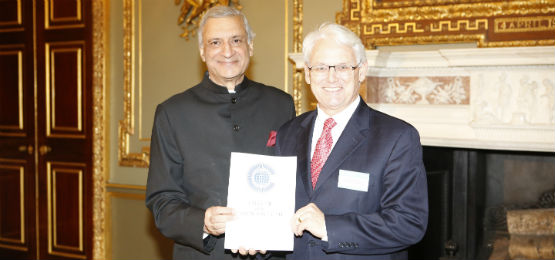

Commonwealth Secretary-General Kamalesh Sharma presents the Commonwealth Charter to Mr Gordon Campbell, High Commissioner for Canada

Given the human rights commitments in this year’s Commonwealth Charter, and next year’s UN world conference on indigenous rights, it would be appropriate for Heads of Government to make a forward-looking statement in their Colombo communiqué. The August 2013 special issue of the Round Table journal lays out current concerns, and a London Senate House conference at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies on 26 September will look ahead to Colombo and next year’s UN event from a Commonwealth perspective. The prime need, for the Commonwealth’s first nations everywhere, is still to guarantee that they can give free, prior and informed consent to potentially fatal changes to their environment and cultures. As often invisible minorities, geographically and ethnically out of the mainstream in states where majorities rule, their cause must not be overlooked if Commonwealth principles are to mean anything.

Richard Bourne is a senior research fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies; Dr Helena Whall was project officer for the Indigenous Rights in the Commonwealth Project.

Information supplied to the authors by Wiveca Stegeborn, PhD candidate in Anthropology,University of Tromsoe, Norway.

very good commonwealth summit.

We were asked to comment via twitter and apologies for the delay in doing so.

It is a very good article and indeed the treatment of the Veddah in Sri Lanka is shocking. Recently three Veddah youths were disappeared in Sri Lanka, as we discussed here: http://blog.srilankacampaign.org/2012/05/disappearance-epidemic.html

However generally speaking the issues relating to the Veddah have been overshadowed by the Sri Lankan Government’s systematic attempts to oppress its Tamil minority (attempts that hit their peak with the mass murder of some 40-70 thousand Tamils during the final stages of the civil war in 2009) and recent concerted attacks on Sri Lankan Muslims and Christians.

Thus the oppression of the Veddah cannot be taken in isolation, but must be seen as part of the ongoing human rights catastrophe in Sri Lanka, and as a symptom of the Sri Lankan Government’s contempt for all its minorities.