By Sir Ronald Sanders KCMG AM, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies and a former Caribbean diplomat

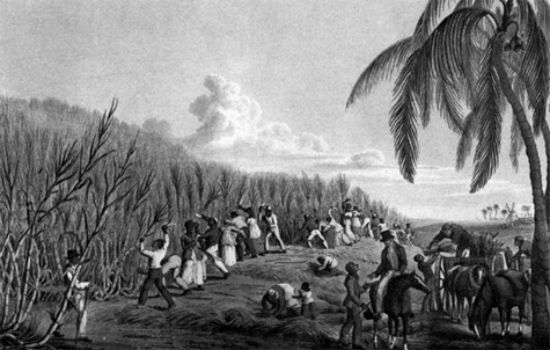

In 1838, British slave owners in the English-Speaking Caribbean received £11.6 billion in today’s value as compensation for the emancipation of their “property” – 655,780 human beings of African descent that they had enslaved and exploited, and, in many cases, brutalised. The freed slaves, by comparison, received nothing in recompense for their dehumanisation, their cruel treatment, the abuse of their labour and the plain injustice of their enslavement.

This is the basis on which 14 governments of the member-states of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) have decided to approach the UK law firm, Leigh Day, “to consider a legal challenge to seek compensation from three European nations for what they claim is the legacy of the Atlantic slave trade”.

The legal challenge – if it is made – will be against Britain, France and The Netherlands.

Uncertainty of legal challenge

It is by no means certain that any legal challenge will be mounted. This accounts for the cautious language of Leigh Day in its formal announcement that it had been “approached” as distinct from “retained” by the Caribbean governments. The lack of certainty also explains the further remarks by Martyn Day of Leigh Day, that: “At this early stage the CARICOM Governments have asked us to advise them on the bringing of a legal claim against the British, French and Dutch governments if they cannot reach a negotiated settlement”.

Exactly who will be negotiating with whom is unclear since none of the three European governments has responded to the statement by CARICOM governments that they will be seeking reparations for slavery. It is also not at all clear which of the 14 CARICOM governments will actually take forward a legal challenge against the three European governments particularly as that, apart from the government of Barbados, they have all shown reluctance to take on bigger powers in costly legal disputes. A particular case in point is their failure to take action against the United States government at the World Trade Organisation over a rum issue. Many of them also fear reprisals from the European powers. So while the demand for reparations for slavery plays well politically with domestic audiences, few Caribbean leaders have shown much enthusiasm for legal action internationally. Indeed, “reparation committees” have only been formed in four of the 14 CARICOM countries. In this regard, the Prime Minister of St Vincent and the Grenadines, Dr Ralph Gonsalves who has written and spoken passionately on the matter, stands out. Perhaps it is because of his awareness that some Caribbean governments may not proceed vigorously against the three European governments that Gonsalves has publicly stated:

“Let us be in no doubt that neo-colonialists, western European states, including Britain, international financial institutions, intelligence agencies from former colonial powers in the Caribbean schooled in the art of political chicanery, and more, will be put in the service of denying just reparation. They will all play it rough: intimidation, divide-and-rule, and subterfuge will be utilised against leaders and those Caribbean nation states which are in the forefront of this monumental reparation cause”.

The Background to the Slavery and Reparations Issue

The monies paid to slaves owners have been studied and assembled by a team of Academics from University College London, including Dr Nick Draper, who spent three years pulling together 46,000 records which they have now launched as an internet database. The website is: ucl.ac.uk/lbs. According to Draper’s findings, the benefits of those monies still exist in Britain today. For example, they are the foundations of Barclays Bank, Lloyds Bank and the Royal Bank of Scotland. They are also the basis of wealth for many leading British and Scottish families among them the Hogg family – two of whom became Lord Chancellors in British governments.

Dr Draper is reported as saying of the Hogg family:

“To have two Lord Chancellors in Britain in the 20th century bearing the name of a slave-owner from British Guiana (now Guyana), who went penniless to British Guiana, came back a very wealthy man and contributed to the formation of this political dynasty, which incorporated his name into their children in recognition – it seems to me to be an illuminating story and a potent example.”

The Hogg family were not unique. The wealth and political good fortune of 19th Century British Prime Minister William Gladstone had its origins in the £83 million, at today’s value, of “compensation” given to his father, John Gladstone, for slaves he owned in British Guiana and Jamaica.

But it was not individual families alone that helped to create African slavery and that benefitted from it; it was the British state as whole – its successive governments that provided subsidies for the trade; that adopted legislation that facilitated it; and that were complicit with the governments of their colonies in adopting laws that designated African slaves as “real estate” – people stripped of human identity, including life, and, therefore, to be treated like land, houses and buildings.

A recent Daily Telegraph (UK) report laid the blame for this squarely at the feet of the Stuart Monarchs Charles II and James II who,

“systematically drew up laws to enforce and spread hereditary slavery… with relentless focus, stacking the courts to ensure favourable rulings, and silence opponents in sedition trials, not least because revenues from tobacco and sugar plantations became the chief source of wealth for the Crown”.

Remarkably, it was also the British State, including the British people, who paid “compensation” to the slave owners while completely disregarding any obligation whatsoever to 655,780 people, who were enslaved and cruelly exploited. To do so, the British government borrowed £20 million which is £76 billion, at today’s value, from the Rothschild Banking Empire. The sum amounted to about 40 per cent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product at the time. As Caribbean Economic Historian, Sir Hilary Beckles points out: “They all recognised that British citizens were socially empowered by the white supremacy culture so effectively institutionalized on a global scale by slave owners”. British exploitation of people in the Caribbean did not start, or end, with the enslavement of Africans. Beckles, records the systematic “elimination” of the Kalinagos – the original people of the Eastern Caribbean islands. It was the first act of genocide in the Western Hemisphere, and it was executed with the full knowledge and approval of the British authorities.

Each of these episodes of subjugation, exploitation and brutalisation of human beings was justified on the racial supremacy of the white race. And while Britain was the principal beneficiary, other European nations shared in the spoils of human degradation. Along with France and the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal were two significant beneficiaries. The latter two countries are not among the European nations that CARICOM countries are targeting because they were not occupiers of, and slave owners in, these particular territories.

Except for the blindest and unrelenting apologists for the acts of genocide and enslavement, it is impossible to discard Beckles’ assertion that these were “crimes against humanity”. As he says:

“The wealth of the (British) Empire required the abandonment of all known laws, conventions, moral parameters, political practices and legal frameworks and the creation of a new and unprecedented labour system”.

When the vast majority of the original people of the Caribbean were extinguished forcing the brutalised handful who remained into submission; when slavery was abolished with no recompense to the Africans for the deprivation of their liberty, the people of the Caribbean were left destitute, deprived and disadvantaged. In Beckles’ words: “They got nothing by way of cash reparations to carry them into freedom. No land grants were provided. No promissory notes were posted”.

The moral case for “reparations” established

That today the people of the Caribbean have built middle-income societies (except Haiti) despite the conditions they were handed at slavery’s abolition, is a tribute to the resilience, capabilities and high quality of human beings that European states considered ‘chattel and real estate’. That they have produced Nobel Prize winners, great athletes and fine intellectual thinkers who have commanded high positions in the international community in business, medicine, the law, and technology is testimony to the wrongness of the “white” supremacist doctrine.

Their achievement re-enforces the position that their enslavement, their servitude and the infamous acts of violence against them were wrong, and it cannot be right that those who were the principal perpetrators of those wrongs benefitted while they were left as nothing more than a human catastrophe.

Today, the Caribbean could have been much further along the road of social and economic development if even half of the “compensation” given to slave owners had been provided to slavery’s victims 175 years ago. There is clearly a moral case for reparations. But can it be prosecuted legally?

Prospects of “Reparations”

Martyn Day of Leigh Day says: “What is an important factor in this potential legal action is that CARICOM is interested in seeking a settlement for the impact of slavery on their communities today – not on the historic position of the individual slaves”. That is just as well. For the question would otherwise have arisen as to how and to whom any “reparations” – either negotiated or awarded by a Court – would be distributed.

If a negotiation with the three European countries fails and the ICJ route becomes impenetrable, another option could be an appeal to the General Assembly of the United Nations. A majority vote may be possible despite opposition from former slave owning countries, including Arab states.

With the moral case so strong, several CARICOM governments would undoubtedly want to take the claim for reparations as far as they can – and the UN General Assembly would give the issue the scale of international attention the issue deserves without involving heavy legal costs that might deter some of them. But none of this should absolve the governments of all the European nations that indulged in slavery, and benefited from it, of the obligation to at least apologise – although Prime Minister Gonsalves has said an apology would not be sufficient.

Ron

This is a very thoughtful and useful perspective which needs to be a factor in the strategic options for the Caribbean governments to explore It seems reasonable to raise the matter at the lelel of the UN General Assembly thereby winning widespread support and momentum for the letigation to follow But then you raise the issue of cost and fear of a backlash from the European powers. One other alternative is this matter flourish in the social media

Eddie, Thanks for this comment. This will be a long and arduous journey. It will require courage without offence and argument without rage. Best wishes, Ron

Sir Ronald: “The mountain is extremely high, the air is very thin, it’s probably unclimable, but we can try, and maybe succed if we go slow and steady” said

Tensing Norgay to Sir Edmond Hillory as they began their epiic assault on Everest.

Cheers: Jack Really enjoyed it, thank you

Dear Jack

Thanks for this profound observation. This particular mountain is high and the climb for those who undertake it will be treacherous.

Best wishes, Ron

Dear Ron

There can be no argument about the inhumanity of slavery and its appalling consequences. Nor that the British State and some families benefited from it hugely.Nor that the emancipated slaves were not helped as they should have been on being freed. The question is what should be done about it 363 years after it was introduced into Barbados. There are many other crimes against humanity which could be brought from history which could also qualify for compensation to the minds of people living to-day. The World is littered with them. Not least of these is the crime of the African leaders who took the slaves prisoner in the first place and sold them to firstly to the Portuguese then the Spanish then to the Dutch French and British and of-course the United States. I would like to return to this subject in greater detail which I would enjoy debating with you but time does not allow to-day.

Yours

Bowen

Dear Bowen

One crime does not justify another as you know. In any event as a commentator on these matters, I prefer not to take sides but to analyse the arguments and the situations. This commentary seeks merely to set out the arguments on both sides while providing the background to the problem and weighing up the likelihood of success.

Best wishes

Ron

My position on this matter is clearly expressed in my versed opinion (I don’t call it a ‘poem’) entitled REPARATIONS FOR WHOM?… and I will re-send it for Sir Ronald’s benefit…. Thanks.

Sir Ronald Sanders’ article expresses the dilemma clearly. The moral case for Middle Passage slavery having been a crime against humanity is clear. It was perpetrated by people and states which regarded themselves and their institutions as civilized. Many, claimed to be guided by the values of religious leaders such as Moses, Jesus and Mohammed. The legal case is not clear, largely because moral issues generally cannot be resolved (or fully resolved) by purely legal means.

So, progress needs to be made politically.

A current example of a live moral issue with long historical roots – including the Indian Ocean slave trade – moving from the legal to the political dimension, is that of the sufferings of the Chagossians. The legal avenues to redress some – only some – of their injustices have been tried; and have been found wanting. If any proof is needed of the difference between the worlds of morality and law, it is provided by the majority (3 to 2) judgement of the highest court in the UK that sending all Chagossians into forced exile from their islands and denying them the right to return was somehow compatible with the UK Government’s obligation under Article 73 of the UN Charter to act in accordance with the principle that “the interests of the inhabitants of these [non self-governing] territories are paramount”.

It is, therefore, encouraging that the government has instituted a review of policy concerning British Indian Ocean Territory [i.e. the Chagos Archipelago, including Diego Garcia]. Many initial views have already been sent to the Review Team*, which I understand will soon become available on a dedicated website. Meanwhile, some contributions on the subject can be found at Richard Dunne’s Chagos Facts Website

https://sites.google.com/site/thechagosarchipelagofacts/home

* contact details:

BIOT Policy Review Team, Room K130, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, King Charles Street, London SW1A 2AH.

Email: BIOT.PolicyReview@fco.gsi.gov.uk

This review of policy addresses a limited area where historic injustices can at last be dealt with through open political processes rather than through an opaque framework of colonial laws. It will be worth seeing if it provides lessons for both the historic slave-trading nations and the descendants and successor states of their slavery-based colonies.

this is a great outlook but it seems progress needs political decisions because of unquestionable power imbalance/bargaining power/ between the would be parties

Ron thanks for sharing your research with us. I see you have some great minds replying to your post. The comments indicate that we should make haste slowly. Some are wise in saying: “There are many other crimes against humanity which could be brought from history which could also qualify for compensation to the minds of people living to-day. The World is littered with them….” “The legal case is not clear, largely because moral issues generally cannot be resolved (or fully resolved) by purely legal means.”

You said “it will require courage without offence and argument without rage.” Those of us who were born and bred in the West Indies, and those who have made the West Indies their home, know the psychological and political scars which many West Indians carry to this day. Perhaps your research is another step in understanding our history and learning from it.

What might be a good out-come for the case of reparation is the continued involvement of Britain, France, Portugal, Spain and Holland in the lives of the peoples of the Caribbean, which they fashioned. It would be good if these States arrive at the point where they see themselves as co-workers in building the people on whose backs they successfully built their empires and enriched their lands. These States and the West Indian people have a shared history. It is time for real change in attitude and involvement in the West Indian people and in those States which were once the masters. Perhaps it will bring about altruistic involvement in the lives of West Indian people and not an exploitative relationship. The present day leaders of these States and West Indian leaders may learn a lesson from history – a lesson we so quickly forget.

Tony

Why should the British people, all of whom have no connection to the slave trade pay for the deeds of their ancestors? If Britain was forced to pay reparations to the Caribbean the entire commonwealth would line up for a drink at the trough. This would only breed hatred and distrust between Britain and commonwealth countries. I would also like to ask this question: As a person of Irish Catholic descent, I assume because of the way my people were treated I would be able to apply for reparations as well? What about Indians or Pakistanis? or Kenyans? Do you see the pattern here? reparations for crimes that happened centuries ago committed by people who are long dead is absolutely bonkers.

This has got to stop now!! this hiding behind- notions that the present population cannot be made responsible for the actions of their ancestors, while those of the enslaved continue to suffer the consequences- while the slavers inheritors continue to benefit from the misery of others. Please peruse:

The Blackest Berry. by W J V Grant…for another perspective on this matter.

I am a decendant of a slave on both paternal and maternal ; when oh when we the talking stop and start the legal action. The arguments for repriation compensation has been discussed for many years.. And yes I think as we are still suffering due to the fore parents of some countries who enslaved us, who reaped the benefit of our suffering; we also should receive compensation from their decendants. Had no corporate slavery happened you may not be in the same position you are today, you maybe worse off . You should thank god you knew for foreparents, your history and your culture. Some of us don’t.