By Mandy Banton, Senior Research Fellow, ICWS; formerly of the UK National Archives

Despite rumours and half-truths long in existence, the official line that no locally created records of former colonial governments were transferred to London at independence was generally accepted, although few would have been so naïve as to believe another claim – that none had been destroyed. In 2011, however, legal proceedings brought against the British Government by elderly Kenyans abused and tortured during the Mau Mau insurgency forced an admission that the FCO held not only a huge cache of papers ‘returned’ from Kenya, but also comparable collections from another 37 former dependencies. The context demonstrated that such ‘migrated’ records are of importance not only to the historian; they may provide a basic source of evidence needed to assert the rights of individual citizens.

A report commissioned by the Foreign Secretary to examine ‘what went wrong and what lessons should we draw?’ led to the transfer of most of this material to the UK National Archives (TNA), where researchers are assessing the extent to which it may add to existing knowledge. It also resulted in the creation of an inventory of other FCO documentation, held in its high-security facility at Hanslope Park, which is shocking in its extent. Whereas the ‘migrated archives’ consist of less than 20,000 files, the so-called ‘special collections’ number in excess of half a million. The exact number has been disputed; UK media picked up the FCO’s initial assessment of 1.2 million, but that includes material – the ‘departmental files’ – not yet due for review and transfer to TNA, as well as some copies of items already in the public domain. Perhaps 600,000 is a more accurate figure. A convenient sleight of hand has ensured that these are now ‘retained’ by the FCO, with the approval of the Lord Chancellor on the advice of his Advisory Council on National Records and Archives, and the department is thus no longer in breach of UK public records legislation.

What are these records?

The huge variety of the material created or collected by the FCO and its predecessors, and a date range of over two centuries, makes an easy answer impossible, and individuals wrestling with the inventory spreadsheet will find their own highlights. In a programme of planning for the eventual release of this material the FCO has stated that over a six-year period it ‘will aim to review all high priority special collection records and to prepare for transfer to TNA all of those records which fall within TNA’s collection policy, subject to legal exemptions’. It has estimated that only about 10% can be considered ‘high priority’. Top of that list are ‘around 4,000 files relating to British nationals who suffered Nazi persecution, and their subsequent claims for compensation’. My personal priorities would focus on records of the Colonial Office, perhaps particularly the 158 files from its Intelligence and Security Department (ISD), dated 1963-68. It was this department, in close discussion with MI5, which led policy on the ‘disposal’ of records of colonial governments at independence, and 16 of its files were transferred last year into the ‘migrated archives’ series. But, according to good archival practice as well as the provisions of the law, ISD files dating from the 1960s should have been reviewed at least fifteen years ago for transfer into the existing Colonial Office records series.

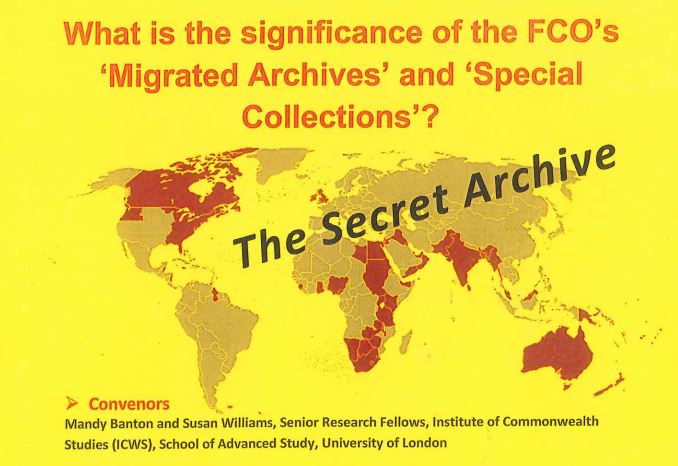

In line with its stated intention to consult widely the FCO is to hold a ‘records day’ on 9 May 2014. On 29 May the Institute of Commonwealth Studies will host a conference entitled “The Secret Archive: what is the significance of the FCO’s ‘migrated archives’ and ‘special collections’?”.

Great how can i get copies of the Mau Mau War in Kenya 1952-1963

John